Islamic calligraphy, or Arabic calligraphy, is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy, based upon the Arabic language and alphabet in the lands sharing a common Islamic cultural heritage.It is derived from the Persian calligraphy. It is known in Arabic as khatt, which derived from the word ‘line’, ‘design’, or ‘construction’.

The traditional instrument of the Arabic calligrapher is the qalam, a pen made of dried reed or bamboo; the ink is often in color, and chosen such that its intensity can vary greatly, so that the greater strokes of the compositions can be very dynamic in their effect.

The Islamic calligraphy is applied on a wide range of decorative mediums other than paper, such as tiles, vessels, carpets, and inscriptions. Before the advent of paper, papyrus and parchment were used for writing. The advent of paper revolutionized calligraphy. While monasteries in Europe treasured a few dozen volumes, libraries in the Muslim world regularly contained hundreds and even thousands of volumes of books.

Coins were another support for calligraphy. Beginning in 692, the Islamic caliphate reformed the coinage of the Near East by replacing visual depiction by words. This was especially true for dinars, or gold coins of high value. Generally the coins were inscribed with quotes from the Qur’an.

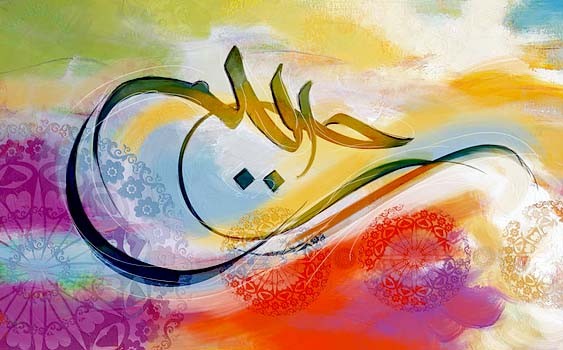

In its June 20, 1980 edition, the daily newspaper Khaleej Times of UAE stated, “Renaissance of Islamic Calligraphy – A mystic artist from Pakistan who has become a legend in his own time. The remarkable story of Sadequain, who did not seek but was endowed with divine inspiration.” Sadequain is arguably responsible for the renaissance of Islamic calligraphy in Pakistan. A review of the history of calligraphic art in the country during the decades of the 1950s and ’60s reveals, that there was minimal activity in this genre of art form. Syed Amjad Ali wrote in his book, Painters of Pakistan, that after Sadequain’s first exhibition of calligraphies in December 1968, “For next fifteen years or sixteen years, a veritable Niagara of painterly Calligraphy flowed from his pen and brush.” He further stated that, “He initiated painterly calligraphy and set the vogue for it in Pakistan.”

Calligraphic art had enjoyed in the past, a revered status in the sub-continent, when it reached the pinnacle during the glorious days of the Mughal Empire. But after the downfall of the empire, calligraphic art became a victim of neglect, and fell so far out of favor that in post-partition Pakistan, it was considered to be a mere vocational skill and not a serious genre of creative art. Searching for a new form of expression, Sadequain commemorated Ghalib’s anniversary by illustrating his poetry in 1968. In order to enhance the paintings, he chanced to inscribe Ghalib’s verses in Urdu to append the paintings, and that experiment later led to more calligraphic inscriptions in the Arabic language. That spontaneous occurrence opened the floodgates and paved the way to widespread adaptation of painterly calligraphy in the country and catapulted Sadequain to a national stature of prominence, which still remains unmatched.

In a manner similar to his figurative paintings, Sadequain followed the same principles in his calligraphic art. His calligraphies represent the most radical departure from the established norms, which had been in place for hundreds of years. The centuries-old guarded traditions, watchful eyes of the religious police, or pitfalls of the uncharted waters did not deter him from going where not many had ventured before him. Undeterred, he invented his own iconography and produced a dizzying array of calligraphical marvels at such large scales that had not been witnessed in recent history. He brought the calligraphic art on an even level with other art forms that were at the time practiced in Pakistan. His art became the most effective ambassador for the country in foreign lands and his impact was so profound, that on a number of occasions, Pakistan was represented in international forums only by Sadequain’s masterpieces.

Sadequain often stated that if he placed end-to-end all the calligraphies that he had painted, they would stretch for several miles. In addition to the countless pieces of calligraphies, special mention must be made of some of Sadequain’s major works, which are spread over Pakistan, India, and the Middle East. He inscribed four versions of complete sets of the beautiful Verse, Sura-e-Rehman; the first two versions of the Verse, which consisted of thirty-one panels, have been preserved, one at Staff College Lahore and one with a private collector. Another version, consisting of forty panels was painted on transparent cellophane, of which he gave away several to his acquaintances, and the remaining were reported in newspapers to have been stolen from the Frere Hall after his death. The forth version of the picturesque Verse was painted on marble slabs, which Sadequain gifted to the citizens of Karachi in an elaborate ceremony held on the lawns of the Frere Hall in 1986. The intent was to place the complete set of 40 marble slabs on permanent display at the Gallery Sadequain situated in the main hall of the Frere Hall. But soon after Sadequain passed away, all forty panels disappeared from the premises, leaving no trace behind; what is worse, no police report was registered neither an official inquiry was launched. During the early 1970s, Sadequain completed several large calligraphies for the historic Lahore Museum, and gifted them to the citizens of Lahore. Eight of these large calligraphic panels, each measuring approximately twenty-by-twenty feet, are on display in the Islamic Gallery of the Museum. He also inscribed Sura-e-Yaseen onto a large wooden panel measuring 260 feet long and gifted it to the Islamic Gallery of the Lahore Museum. A large calligraphic mural adorns the power station at Abu Dhabi, which Sadequain completed in 1980.

During the end of 1981 through 1982, Sadequain stayed in India for one year, and painted several large calligraphic paintings and murals. One of the most significant calligraphic works was the rendition of the ninety-nine panels of Asma-e-Husna (The Beautiful Names of God) that he inscribed on the circular wall of the rotunda, which towers an imposing five stories high in the Indian Institute of Islamic Studies at Delhi. The approximate length of this calligraphic work is seven hundred feet and the surface area is close to 3,000 square feet. This rendition of 99 panels of Asma-e-Husna is one of the three complete sets he finished in his life. In addition to the calligraphic work at the Indian Institute of Islamic Studies at Delhi, Sadequain painted or sculpted several other calligraphic works in India at Aligarh Muslim University, Ghalib Academy, Jamia Millia, and the Tomb of Tipu Sultan. In his customary practice, Sadequain gifted all this work to the Indian authorities. In addition to painting the murals and calligraphies in India, he exhibited his works at Delhi, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Aligarh, Banaras, and several other cities.

A reason of concern; scores of Sadequain’s masterpieces have disappeared and the ones that remain, show signs of decay. Farhana Rizvi documents in her master’s thesis, her trail to locate one of Sadequain’s murals, which at one time adorned the halls of a prestigious institution. After a long pursuit, she discovered the mural was condemned to a garage, which also housed diesel vehicles. “The constant exposure to diesel fumes,” she stated, “had left black carbon deposits so deep that it was difficult to make out the forms and figures.”

Related posts:

Sadequain’s Calligraphy

Sadequain’s Calligraphy

Sadequain and Calligraphic Modernism

Sadequain and Calligraphic Modernism

Sindh Handicrafts

Sindh Handicrafts

10 Most Beautiful Mosques (Masjids) in the World

10 Most Beautiful Mosques (Masjids) in the World

10 Famous Masjids (Mosques) in Pakistan

10 Famous Masjids (Mosques) in Pakistan

Baitul Aman Masjid (Mosque) in Barisal – Bangladesh (Photos)

Baitul Aman Masjid (Mosque) in Barisal – Bangladesh (Photos)

Top 5 Largest Masjids (Mosques) in India (with Photos)

Top 5 Largest Masjids (Mosques) in India (with Photos)

BRAIN (First PC Virus in History) Video

BRAIN (First PC Virus in History) Video

Playing with Architecture in Munich (Photos)

Playing with Architecture in Munich (Photos)

Top 10 Tallest Buildings in Pakistan According to Height (Photos)

Top 10 Tallest Buildings in Pakistan According to Height (Photos)

September 1965 Pak India War (Miscellaneous Photos) – Part-I

September 1965 Pak India War (Miscellaneous Photos) – Part-I

Top 15 Most Dangerous Hanging Suspension Bridge of Pakistan (with Photos)

Top 15 Most Dangerous Hanging Suspension Bridge of Pakistan (with Photos)